John Adams: The Last Nonpartisan President

In the biography John Adams by renowned historian David McCullough (1776, Truman, The Wright Brothers), readers get what the cover promises: the tale of that largely forgotten Founding Father and President, from his inauspicious start as the son of a Massachusetts farmer to his glorious finish at the age of 90 on July 4th, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, with every virtue and foible on full display for both history and readers to pass judgment on.

Coming in at 656 pages (Source Notes, Bibliography, and Index not included), this Pulitzer Prize winning sojourn into the life of the famed New Englander spares no known detail that may have influenced Adams on his path to becoming a patriot and politician, a partner and parent. Readers get nothing less than the life of a great man who rose above the burgeoning of party politics as his predecessor George Washington had urged, a wondrous accomplishment that both marked him as a true civil servant for posterity and yet sealed his fate as a public figure among his contemporaries.

McCullough structures his telling into three parts: (I) Revolution; (II) Distant Shores, & (III) Independence Forever.

In Revolution, Adams’ childhood, his education as a lawyer, and his rise to prominence as a member of the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence (as well as its editor) are presented. His willingness to defend the British soldiers who perpetrated the Boston Massacre when no other lawyer would, when his colors as a “true blue” patriot might have been brought into question, is offered as irrefutable, substantiated proof of his impartiality, his sense of duty, and his belief in justice for all. His bravery as a representative of the Continental Congress walking along with both Benjamin Franklin and Edward Rutledge into the hands of the British, despite his personal belief that General Howe had “Machiavellian maneuvers” in mind (which fortunately the general did not), spoke to Adams’ willingness to put his life on the line, even against his better judgment, if his nation called on him to serve.

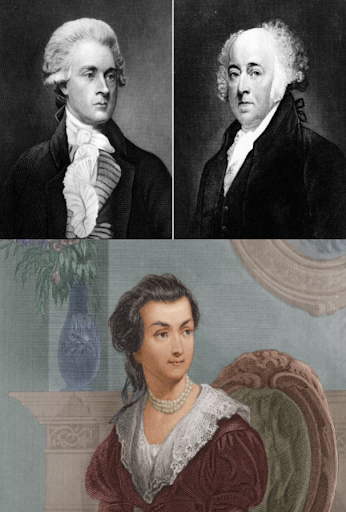

Top left: Thomas Jefferson. Top Right: John Adams. Bottom panel: Abigail Adams

In Distant Shores, McCullough reveals a major, as often miserable as it was vital, part of Adams career, a part few readers will be familiar with. Adams served as an ambassador to France, England, and the Dutch from 1777 to 1788, having to watch both the Revolutionary War & the drafting of the Constitution from the other side of the Atlantic, with only one brief return to home of three months. He was even without the company of his beloved wife Abigail for 8 years of his service abroad. Adams’ terrifying first transatlantic voyage on the Boston with storms, British attacks, and leaks aplenty, yet with safe arrival to France, foretold the awful struggle Adams would endure abroad and yet would end to great success, securing both the diplomatic recognition of his nation and vital loans to sustain the fledgling United States. It is also in this section where the deep friendship of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson is on full display, their philosophical & economic differences aside, with their weeks-long tour of English gardens together after the war a crescendo to a relationship that had brought both men (and their families) much benefit and gratitude.

However, no correspondence of the time, not even their own, reached more into the minds of Jefferson and Adams at this time than their letters with Abigail, who maintained correspondence with both men, as well as a plethora of other Founding Fathers, throughout the Revolutionary period. McCullough presents in great detail why Abigail should be credited in large part for Adams’ success. She afforded John Adams the privilege of going abroad, of studying, and of politicking without concern for his domestic affairs. She was solely responsible in his frequent absence for childcare, primary education, managing their farm, and investing their money, all things she did exceptionally well. Even her significant familial & economic contributions to Adams arguably pale in comparison to her words of wisdom for him. She did not merely provide support & solace in times of difficulty through written word. Abigail provided insightful, savvy, and sound advice in matters of politics and policy, and also manage to provide any useful intel she received from her many correspondents. And thankfully, Adams was keenly aware of the fact that, in both in marriage and in intellect, Abigail was his equal.

HBO’s John Adams and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton

The final part, Independence Forever, covers an expansive time period (1788 - 1826) that McCullough tackles coherently and proportionately, despite covering six presidencies, including both Adams’ and his son John Quincy Adams’, as well as the death of his wife, his estranged son Charles, his beloved daughter also named Abigail (“Nabby”). Readers bear witness & may find themselves hostile, towards a changed Thomas Jefferson, a man warped by the grief of his loss of his wife & his daughter, by his extended solitude in Monticello, and by the weight of his crippling & ever increasing personal debt. Jefferson plays prominently as the likely antithesis and antagonist to Adams. As a leader of the Republicans (Adams was nominally a Federalist), as ardent voice of alliance with France (Adams was for England), and as politically Machiavellian as Adams was stoically Washingtonian, Jefferson had become entirely a creature of party politics as we would recognize them today. Intransigent in his opinions. Dialectic in his coloring of American politics. Vitriolic (or at least as what passed for vitriol in that markedly polite times of American discourse) in his private correspondence and in his financial support of openly offensive & scandalous journalism.

However, for all the tragic animosity that came between those two friends, no greater villain presented himself to Adams than the man who ostensibly should have been, in a partisan sense, his greatest ally after Washington’s death: Alexander Hamilton. Adams believed Hamilton a rapscallion bent on becoming the supreme military leader after Washington’s demise with the intent of becoming an American Caesar. Unlike Cicero failing to purge the Roman Senate of Julius Caesar for his ostensible support of the Catiline conspirators, then President Adams decisively eliminated Hamilton’s military prospects. The sidelining of the young New Yorker may have been unnecessary, however. Soon after, Hamilton imploded his own political prospects through the revelation of a scandalous affair (of which Lin-Manuel Miranda’s awarding winning musical offers all the theatrical and bawdy details, and in song no less).

In all three parts of the book, however, certain overarching conclusions can be drawn of Adams. His passion for reading and education, his endless love for his extraordinary wife Abigail, and his seemingly boundless devotion to his fledgling country are perhaps the most prominent of takeaways. His failings were an occasionally explosive temperament (his vocal dressing down of two cabinet members resulting in one’s resignation and the other’s firing), and an apparent inability (or unwillingness) to hold both rhetorical and strategic thinking as equally worthy considerations for a leader as logical and moral thinking. His initial mangling of his role as Vice-President of President of the Senate, particularly the weeks-long debates over what to call the U.S. President (“Your Grace,” “Your Highness,” “His Excellency,” and finally “Mr. President”) perhaps permanently crippled the office of Vice-President into one that is often ignored by both the Senate and the President.

As President, readers will see his greatest blunder as not vetoing the Alien & Sedition Act, an act which sought to expel foreigners and punish anyone writing “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the U.S. government with imprisonment and a fine. The law so blatantly contradicted the First Amendment of the Constitution, this reviewer wishes nothing more than to sit with the ghost of John Adams and scream, “How did you allow this blasphemy to proceed unimpeded?” McCullough, in all his research, failed to supply much in the way of hindsight sympathy for Adams. The context the author supplies is “tumult and fear” of the French, with whom war seemed imminent, but McCullough does admit “the real and obvious intent [of the Federalists] was to stifle the Republican press.”

Chief Justice John Marshall

Of his victories, however, there are a few. First, Adams throughout his political life had advocated for a strong American naval presence as the key to United States security, and as president, he did effectively become the Father of the Navy, which proved to be immensely useful after his presidency in defeating the Barbary Pirates and then later the British during the War of 1812. His second success was his prevention of war with France, something that during his presidency the majority of the nation was clamoring for. The insult paid to America diplomatically during the XYZ Affair (in which American diplomats were told they had to bribe the French $250,000 dollars, the modern equivalent of $5 million dollars), and militarily in France’s unprovoked attacks on American merchant vessels had raised the war cry, and only Adams’ stalwart determination to avoid war, and trust in his longtime friend & diplomat Elbridge Gerry, secured a legitimate peace agreement from France, saving the United States from what would surely have been a devastating conflict, one that may have doomed the young nation in its second fight against England just a few years later. And while the third success is arguably his greatest, it is also his most inadvertent. With just over one month left as president, John Adams appointed John Marshall as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Marshall would serve on the bench for 34 years. In his time, Chief Justice Marshall would determine the character of the Supreme Court, supplying it with both the dignity and authority that the definitively weakest of the three branches of U.S. government so desperately needed, thus turning it into the Court we know today.

None of these great acts would win Adams a second term as president. He had burned too many bridges within his own party. He also refused to campaign in any capacity. And yet Adams was still close at the final tally, finishing with 65 electoral votes to Jefferson and Aaron Burr’s tie at 73. Despite their now public feud, Adams privately supported Jefferson over the ambitious & far less qualified Burr in the resulting deadlock, a deadlock which was only broken through Hamilton’s manipulations against Burr, and thus in his archival Jefferson’s favor. It would be the final straw that would drive Burr to challenge Hamilton to their famous duel and kill him.

Adams, however, did not miss the presidency. He went on to relish a long, joyful retirement of over 25 years, a retirement that would eventually see a rapprochement with his old friend Jefferson. Their robust and frequent correspondence resumed during their final years, a final written testament to their extraordinary careers in extraordinary times, before both men died within hours of each other on July 4, 1826, a fitting end for these heroes of the republic.

Bust of John Adams that Jefferson kept at Monticello in the last year of his life.

Of final note, as a hallmark of all great biographies, readers also become privy to personal details that make the “Colossus of Independence” John Adams into a living, breathing person, even if an extraordinary one. For example, learning that Adams claimed his lifelong habit of having a mug of hard cider at breakfast was thanks to Harvard, the school serving heavily salted meats and fish for meals, is both humanizing and hilarious. Learning that Adams never had the chance or desire to reconcile with his once beloved son Charles, an alcoholic derelict who died an early death after squandering his brother’s money and abandoning his wife and children, is similarly humanizing but utterly tragic.

Whether McCullough’s book has since revitalized the legacy of John Adams in the mind of modern Americans is a dubious proposition. However, it will forever stand as a tribute and reminder to anyone who picks it up that Adams was an intellectual and moral titan, who overcame each political and personal hardship for the sake of his country time and time again. Adams will thus likewise forever stand as an example for all citizens and civil servants to look to for civic virtue, whether as a blueprint for doing what is right in the face of the pressure to do what is popular, or for acting in the public’s interest when the temptation of self-interest is at its most alluring.

Ethan Dazelle is a Policy & Law Advisor at the U.S. Department of Labor. When he is not writing book reviews for PMAA, Ethan is researching and writing on human rights, international law, & just about anything else that piques his interest. Check out Ethan’s other PMAA posts.